mE & ALi: mY LIFE WITH THE GREATESt

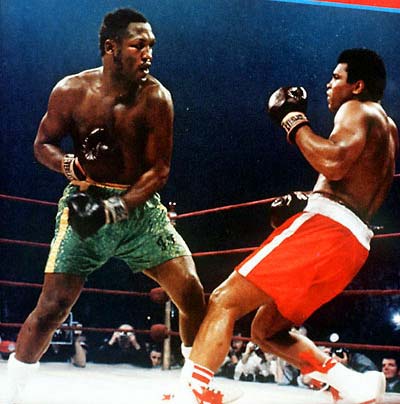

nEW YORK, March 8 – In Madison Square Garden 30 years ago,

the rebel suspended from work for claiming "no quarrel with them

Viet Cong" returned to settle up with a former meat packer who routinely

soaked his face in brine.

A Montreal snowstorm closed school that morning, giving me enough unsupervised

time to empty my $45 in life savings for two closed circuit fight tickets

at the Forum. I felt so proud as the clerk handed me those tickets, confirming

that chubby fourth graders with crappy math grades are real people too.

The moment marked my first public act free from adult direction. Launching

ScreedMe marked my second.

I trudged home to invite my father to "The Fight of the Century"

between Joe Frazier and the other black guy who’s name I couldn’t

pronounce but who used to be called Cassius Clay, until it got him arrested

… or something like that. I’d never "invited" anyone

to anything. This was no ordinary snow-day.

During the fight that night I got to know Muhammad Ali so well that Joe

Frazier’s amazing 15th round hook slamming Ali to the canvas hurt

me too. Ali lost, Frazier won, I cried, and my mother asked if I’d

done my homework.

The next day at school I heard some teachers chortle that, "bigmouth

Ali got what he deserved."

I hated those teachers. The side you took in the Ali-Frazier fight became

my test for friend or foe. I’d pin hapless friends of my parents

who stopped by to pick up sugar or drop something off, asking who they

had "wanted to win?" Answering "Frazier" drew a scowl

and a diatribe on why they were wrong or even "stupid" in one

case. My parents asked me to stop answering the door.

Soon I was taping picture cutouts of Ali and his fights across my bedroom

walls and reading all about Elijah Muhammad, or "Is-Lamb" as

I pronounced it. My parents told me I should study math. Instead I started

running and pushups, lost the chubby thing, and asked my parents if I

could go to a summer boxing camp?

After three years of more boxing and not enough math I closed the sports

pages before finishing the story. Rushing to my father’s dressing

table, scraping together all the loose change I could find, I was soon

looking up at the sweaty crowd jammed with me into the 24 heading downtown.

Hopping off the bus outside Le Chateau Champlain, I squinted up at all

those glinting half-moons – thirty six floors of glinting half-moons

against a blue sky and three clouds. A nearby bank flashed date, time,

and temperature: July 15, 1974 - 11:07 AM - 28C

Checking with la concierge, I frowned, as adults did when they had something

important to say, and croaked my deepest imitation of post-pubescent authority.

"Qui, bonjour. La chambre de M. Ali. Muhammad Ali. Pouvez-vous s’appeler,

s’il vous plait. M. Kippen est ici. Uh, je suis … M. Kippen."

Peering down, la concierge eyed me like a disapproving teacher as she

rang. Looking up, I watched her without a blink as she dialed.

"Je m’excuse," she nodded after half a dozen rings, "il

n’y a pas de reponse - No answer sir."

Sir!? That croaking must be working. But there was no time for flattery.

I had to think fast. If he wasn’t here that meant he was out, and

if he was out, that meant he’d be back - right? Yes, he’d have

to come back. So I walked over to one of the oversized, overstuffed, green

sofas, with little gold tassels hanging along its velvet sides. The overhead

hotel sound system played a piano version of "Do The Hustle."

For a few minutes I sat and peered out of the lobby’s two-story high

glass windows onto the street, then looked over at a wall clock - 11:20

AM.

Taxis, buses, and tourists came, went, and whatever. I kept watching and

waiting. Eventually, I looked back at that clock again- 12:03 PM.

The hotel was busy but I didn’t really notice. I could only really

think about all the questions I needed to ask to grow up just like him,

do what he did, wear what he wore, win like he won, drive my teachers

crazy like he drove my teachers crazy - that would be the best part.

I looked back at the clock - 2:30 PM. Did I miss him? By now that clock

was starting to look back at me.

Another taxi pulled up outside those giant windows, but this one was different.

Three men sat inside. Three black men, one with a short flattop haircut

and a suit - a white shirt and a dark suit. He began to unfold himself

from the inside. My breathing stopped - 2:31. As he straightened to stand,

so did I. He was tall. I strained every face and eye muscle to focus.

Now out of the taxi, he started to walk.

Yup - that was him! He headed toward the revolving hotel doors. I inched

toward the entrance, stopped, then scrambled to those revolving doors,

quickly planting my feet in front of them, staring up, stretching out

my arm - waiting.

He climbed the outside hotel steps, soon revolved through those doors,

stopped in front of me and looked down.

"Hello Mr. Ali. My name’s Alexander Kippen and I’ve been

waiting here all day to meet you."

Holding a book in one hand, Muhammad Ali lifted his other arm slowly like

heavy timber, gently squeezing my hand.

"Hello young man," he murmured and ambled past, followed by

two black men in knit caps, bellbottoms, and collarless shirts.

I followed as they strode through the lobby, all filing into the elevator.

First one inside, Ali turned, leaned lazily against the back elevator

wall, then looked straight at me as I froze at the elevator edge.

… "Well c’mon." He slowly waved his hand inward .

I hopped inside as the doors slid shut with a ring.

The two men in knit-caps talked and Ali read as we rode into the sky.

Somewhere along the way he peeked over his book and looked down at me

as I looked up at him, then widened his eyes, leant forward and cocked

his head for emphasize.

"So you’re an Aliii fan huh?"

I nodded urgently, without blinking - or breathing.

At floor 35, the doors opened with another ring. Everyone slowly filed

out and into Ali’s suite around the corner. I entered last. I couldn’t

believe it.

The place looked like a giant apartment - big white walls, thick green

carpet, dark oak furniture, and a long red sofa. You could see the city

skyline through one of those big half-moon windows at the far end of the

room. Ali dropped into the red sofa with his book, while the two men in

knit caps sat at a nearby table. I took a chair across the room.

Ali read, the two men talked, I stared.

The two men talked of devils and angels, of Allah’s greatness and

human sin. I noticed now that Ali was reading the Koran. They had all

spent the day praying at a Montreal mosque.

This was my chance. I knew about the Koran, about Is-lamb, Mecca and Malcolm

X, of Herbert and Wallace Muhammad, their father Elijah "The Messenger,"

and his White Devil theory of evolution.

I’d read "Ring," "Boxing Illustrated," and countless

other sports magazines following Ali. I’d traveled the world in those

magazines, learning about every foreign place where Ali fought. I’d

studied religion and political theory in those magazines too, at least

Ali’s ideas on religion and political theory.

He was set to fight 26 year-old George Forman for the heavyweight title

that Fall in Zaire, a country I pronounced as "Zayr". Still,

I knew that Kinshasa was once called Leopoldville before the Congolese

booted their Belgian overlords. I knew that President Mobutu Sese Seko’s

full name translated into something like "Mobutu the unbeatable warrior,

who through his indomitable spirit and will to win, will move from triumph

to triumph, leaving fire in his wake." Pretty cool. At school, I’d

started attaching titles like that to my name. It drove my Geography teacher

crazy.

"Is that Black Muzzlim stuff you guys are talking about?" I

cut in.

"Uh … Excuse me young man?"

"You’re talking about Black Muzzlim stuff right? Allah, White

Devils?"

Earlier that week at breakfast, my father had watched me warily as I painstakingly

explained White Devil evolution.

"I see" he finally said between cereal spoonfuls, "so -

are you a White Devil?"

I looked down at my napkin. "I don’t think so. But I’ll

check."

Ali looked up. The two men looked at each other.

"I believe the young brother refers to the Nation of Islam,"

said one of the knit-capped men, stretching out the last word for emphasis.

"Yeah," I sat back with a little smile, "Is-lamb. Black

Muzzlims."

The men in knit-caps looked at me re-assuringly.

"Well, the media likes to assign us the term Black Muslims, in what

we refer to more accurately as the Nation of Islam," again stretching

out the last word.

"Oh."

After further discussion between the men and me, ranging from Ezzard Charles

to my plans after graduation a decade away, they stood up and looked over

at Ali.

"Well champ, we know you need your rest so we’ll leave you alone."

Then they turned to me. "Young man?"

"That’s OK," I blurted, "I’ll stay."

Before the two men could insist, Ali waved them off casually.

"It’s alright, he’s OK. Just a little fan. I’ll give

him a few minutes."

The men nodded agreeably then walked out, leaving Ali and me alone. Ali

and me. I couldn’t believe it. That breathing problem came back.

… "So, Alexander – you in school?"

I coughed, I think. "Yup - I win bets with all the kids on your fights.

I’m going to bet ‘em all again this Fall when you fight George

Forman."

"Geeeeoooorgggge Forman." Ali stretched the name lazily.

"What’re you going to do to him? You’re fighting in Zaire

right? Rumble in the Jungle? How you going to …"

Ali waved me off like a stray fly. "Geeeeoooorge Forman don’t

matter."

"… He don’t?"

"He don’t matter at all," Ali repeated, inhaled, then gazed

out the half-moon window. A little cloud sat nearby.

"Well, what if you …"

"Listen, young man." He held up his hand. "How much time

and money, how many great minds, years of study, great schools, how much

powerful equipment, steel, glass, concrete did it take just so we could

sit up here and talk in the sky?"

I looked outside the half moon window at that cloud.

"All those minds, all that money, all that study, all that time just

so we could sit up here and talk in the sky," he added.

I nodded seriously.

"All that - but in just a few seconds …"

I watched closely as Ali twirled his index finger, making a whooshing

sound – "...in just a few seconds, Allah could blow it all away."

He sat back quietly into the long sofa clutching his Koran.

"Allah could just blow it all away. That’s why George Forman

don’t matter."

Ali shocked most of the world that October, when he knocked George Forman

out in a stadium that still stands today, barely, as testament to a time

when Mobutu reigned and Disco had yet to reach its peak. But Ali didn’t

shock me.

I won hundreds in bets at school, stuffing so many dollars and coins into

my pockets the day after Ali won, I was sure I’d never need another

paper route. My French teacher kicked me out of class that day, barking,

"impossible, absolument, impossible."

Impossible, just like Ali.

Years passed. Ali retired, Foreman made a comeback, Disco peaked, fell,

then made a quick comeback of its own. Not so for Mobutu. He died. I grew

up.

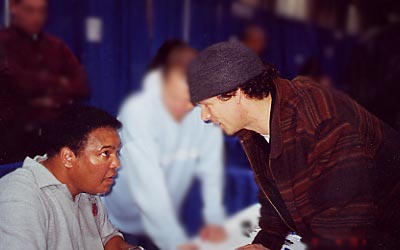

I thought about my afternoon with Ali when I saw him shakily clutch the

Olympic torch in Atlanta. I thought about our little talk when I watched

the Ali-Foreman documentary When We Were Kings. I thought about

it when Ali finally apologized for all the terrible names he called Joe

Frazier. I thought about it when I went to a giant sports promotion in

New Jersey this month carrying an old Ali photograph for him to autograph.

I still think of Ali and that day. I wonder if a kid today could ever

get that close to a superstar. Could a mini Alexander sit in a hotel room

for half an hour with Michael Jordan? I think about that day a lot, about

what has become of Ali and Foreman, and of the world a quarter-century

since.

George Foreman did matter of course. He mattered a lot. Rocky Marciano,

Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier, Larry Holmes, Mike Tyson. Guys like these always

matter. Me? I still hope to grow up to become the Ali of my dreams. But

I already understand what Ali meant.

Yours Truly,

Xandor

Copy Boy In-Chief

![]()

Copyright © 2001